- Home

- Jason Y. Ng

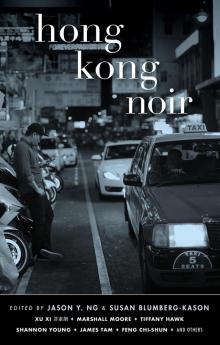

Hong Kong Noir

Hong Kong Noir Read online

Table of Contents

___________________

Introduction

PART I: HUNGRY GHOSTS & TROUBLED SPIRITS

Ghost of Yulan Past

Jason Y. Ng

Tin Hau

TST

Xu Xi

Tsim Sha Tsui

This Quintessence of Dust

Marshall Moore

Cheung Chau

The Kamikaze Caves

Brittani Sonnenberg

Lamma Island

PART II: OBEDIENCE & RESPECT

You Deserve More

Tiffany Hawk

Lan Kwai Fong

Phoenix Moon

James Tam

Mong Kok

One Marriage, Two People

Rhiannon Jenkins Tsang

Ma On Shan

PART III: FAMILY MATTERS

Ticket Home

Charles Philipp Martin

Yau Ma Tei

A View to Die For

Christina Liang

Repulse Bay

Expensive Tissue Paper

Feng Chi-shun

Diamond Hill

PART IV: DEATH & THEREAFTER

Blood on the Steps

Shannon Young

The Pottinger Steps

Kam Tin Red

Shen Jian

Kam Tin

Fourteen

Carmen Suen

Wah Fu

Big Hotel

Ysabelle Cheung

North Point

About the Contributors

Bonus Materials

Excerpt from USA NOIR edited by Johnny Temple

Also in Akashic Noir Series

Akashic Noir Series Awards & Recognition

About Akashic Books

Copyrights & Credits

For my fellow Hong Kongers, alive and dead.

—JYN

For Tom, for bringing me back.

—SBK

INTRODUCTION

Behind the Neon Lights

Fourteen.

That number is about as bad as it gets in Hong Kong. Pronounced “sup say” in Cantonese, the city’s lingua franca, the ominous word sounds like “sut say”—which means certain death. It is so universally avoided that buildings have no fourteenth floor and people stay clear of cell phone numbers, license plates, and hotel rooms with that inauspicious combination of digits. Think about the myth surrounding unlucky thirteen in the West, amplify that a thousand times, and you’ll start to get the idea.

So when Akashic Books suggested that we put together fourteen stories for a Hong Kong noir volume, we cringed. Choy! as older folks in Hong Kong like to say when they hear something sacrilegious, before they spit on the floor and shoot the offender a dirty look.

Then it clicked. Of course. It has to be. What would the city’s first noir volume be without the most forbidding of all numbers? A collection of dark tales set in Hong Kong must have fourteen stories—no fewer and no more. Call it foresight or blind luck, the publisher had gotten it dead right.

But unlucky numbers are hardly the only ominous thing that Hong Kong has to offer. Going back two centuries when it was a sleepy fishing village on the underbelly of imperial China, Hong Kong was rife with pirates roaming the South China Sea. Once the British snatched Hong Kong—after not one but two wars with the Middle Kingdom—they built it up with opium money. Conglomerates in modern-day Hong Kong like Jardine, Swire, Wheelock, and Wharf started out as drug pushers to a country that never wanted opium in the first place. With checkered beginnings like this, it is little wonder that Hong Kong has always had a dark side that persists to this day.

Sun Yat-sen, the father of modern China, spoke Cantonese as his mother tongue and spent his formative years in Hong Kong in the late nineteenth century. It was there he and likeminded rebels plotted an empire-ending revolution against the Qing Court. Soon, with its laissez-faire environment, Hong Kong became home to Jews, Russians, Parsees, Gurkhas, Hindus, and other foreigners seeking new starts and business opportunities. When the Second World War reached East Asia, Hong Kong became a refuge for mainland Chinese fleeing Japanese invaders. And on Christmas Day in 1941, the city fell and so began one of the darkest chapters in its colonial history. During the occupation, Japanese collaborators and the Allied resistance played dangerous games of espionage in Hong Kong, risking it all to outlast and outmaneuver each other. It is against those tumultuous times that Brittani Sonnenberg set her haunting story included here, “The Kamikaze Caves.”

Hong Kong began to recover and thrive after the war ended, as mainland migrants from wealthy businessmen to skilled artisans and poor peasants continued to pour into the British-governed city, while the Communists fought the nationalist government in a bloody civil war. It was then that monikers like the Fragrant Harbor, the Pearl of the Orient, Shoppers’ Paradise, and Asia’s Little Dragon were coined. Feng Chi-shun describes the 1950s in his story, “Expensive Tissue Paper,” which is set in a neighborhood of mostly Shanghai immigrants aptly called Diamond Hill.

Hong Kong continued to benefit from the southern migration, as refugees swam across the Shenzhen River in search of safety and opportunities. Mainlanders overran the border during Mao Zedong’s epic land reform and the Great Leap Forward, a man-made famine that reportedly took forty-five million lives between 1958 and 1962. Enter Hong Kong’s “Belle Epoque.” The West learned about this exotic southern belle through Hollywood romances like Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing and noir films such as Hong Kong Confidential and The Scavengers.

Hong Kong’s “Golden Age” was a period of rapid urbanization. Infrastructure projects began with the construction of public estates, subsidized apartment blocks in which hundreds of thousands of hillside squatters—as seen in Hollywood’s The World of Suzie Wong—were resettled. It was one of the colonial government’s most ambitious and proudest campaigns. Carmen Suen’s story, “Fourteen,” takes place in the first public housing estate to have its own bathroom and kitchen in every unit.

The fifties and sixties were also an era of R&R mayhem during the Vietnam War, which comes alive in Xu Xi’s “TST,” about a young girl in the world’s oldest profession. James Tam writes a dark yet comical account of another lady of the evening in the gritty and populous Mong Kok district. Sexual exoticism came to a halt in 1967, when leftist riots broke out in Hong Kong shortly after the Cultural Revolution began to ravage China. Shen Jian writes about those eight months of bomb scares and street violence in his story, “Kam Tin Red,” and how one local family was torn apart.

The early 1970s saw the peak of police corruption, which resulted in the Independent Commission Against Corruption, an agency created to investigate dirty cops and bring order to law enforcement. At the same time, the Royal Hong Kong Police Force began to hire more local Chinese and fewer British cops to address widespread discrimination and improve public relations with the hoi polloi. Charles Philipp Martin’s story, “Ticket Home,” brings the reader into the last few years of the Royal Hong Kong Police Force, before the word Royal was eventually dropped in 1997, when the city was handed back to the Communist regime under the promise of “one country, two systems.”

We relive the handover in Rhiannon Jenkins Tsang’s story, “One Country, Two People,” which takes place in Ma On Shan in the New Territories, while Tiffany Hawk flashes back between the handover and the present day in “You Deserve More,” set in the rowdy expat enclave of Lan Kwai Fong. And on the subject of expats, Christina Liang writes about domestic drama in Hong Kong Island’s luxurious Repulse Bay in “A View to Die For.”

Hong Kong’s sordid history notwithstanding, the city remains one of the safest in the world. In a place that never sleeps and barely even blinks, violent crimes are a relative

rarity and people feel safe hanging out on the street at all hours of the day. When Hong Kongers do commit murder, however, they do so with plenty of dramatic flourish. Dismemberment, cannibalism, a laced milkshake, and a severed head tucked inside a giant Hello Kitty doll—Hong Kongers have seen it all. The media always has a field day with homicides, splashing gory photos and fifty-point-font headlines on the front page. Shannon Young sensationalizes a grisly murder in “Blood on the Steps,” set on Hong Kong Island’s fabled Pottinger Street. Marshall Moore memorializes gruesome suicides on the outlying island of Cheung Chau in his story, “This Quintessence of Dust,” and Ysabelle Cheung’s story, “Big Hotel,” takes place at an eerie funeral florist shop in North Point.

As coeditors, we come from two very different backgrounds. Jason was born in Hong Kong and spent his formative years in Europe and North America before moving back to his birthplace to rediscover his roots. Susan was born and raised in the United States and lives there now, but spent her formative years in Hong Kong and mainland China. What brought the two of us together was our love of Hong Kong and its history, culture, and freedom. The city may be far from perfect, but there is a bounty of quirks to make writers like us constantly feel like kids in a candy shop.

All across the city, for instance, you can find little shrines dedicated to Tudigong—the God of the Ground—placed in front of retail shops and outside residential homes, complete with burning incense and a pyramid of Sunkist oranges. Religious holidays such as Buddha’s birthday, Christmas, and Yulan—the Taoist Festival of the Hungry Ghosts—are observed in secular Hong Kong with equal zeal. Jason brings alive Tudigong, Yulan, and other elements of the local folk belief system in his story, “Ghost of Yulan Past.”

Jason’s story also takes us to the present day, Hong Kong’s darkest era yet. His tale alludes to the Umbrella Movement in 2014, during which student activists occupied large swaths of the city for months on end to demand universal suffrage and oppose the Chinese government’s increasing interference in local politics. Since then, many young activists have been jailed for their involvement in the movement, and publishers of books critical of the Communist leadership have been kidnapped, only to reappear on the mainland in staged confessional videos. The city’s future is murky and the rights enshrined in the Basic Law—the constitution governing Hong Kong for the first fifty years after the handover—are being chipped away by the day. Twenty years into the handover, the Sword of Damocles that hangs over the city’s heads is inching ever closer.

So what will Hong Kong look like in five years, ten years, or thirty years—when the “one country, two systems” promise expires? It’s impossible to foresee. Hong Kong’s future may not be within our control, but some things are. We can continue to write about our beloved city and work our hardest to preserve it in words. When we asked our contributors to write their noir stories, we didn’t give them specific content guidelines other than to make sure their stories end on a dark note. What we received was a brilliant collection of ghost stories, murder mysteries, domestic dramas, cops-and-robbers tales, and historical thrillers that capture Hong Kong in all its dark glory. The result is every bit as eclectic, quirky, and delightful as the city they write about.

So bring on the fourteen.

Jason Y. Ng & Susan Blumberg-Kason

September 2018

PART I

HUNGRY GHOSTS & TROUBLED SPIRITS

GHOST OF YULAN PAST

by Jason Y. Ng

Tin Hau

Choi gives the faded red door a hefty push and it creaks like a rusty old ship. He puts one foot across the granite threshold and pokes his head in.

“Hello?”

A thick whiff of burning incense hits him before his eyes adjust to the temple’s dark interior. A giant statue of Tin Hau—the Taoist Goddess of the Sea—snaps into view, her calming face drenched in the altar’s crimson light and her commanding figure flanked by a pair of porcelain guards.

“Anyone there?”

“We’re already closed,” a woman’s voice echoes through the airy hollow of the foyer. “Come back tomorrow. The temple opens daily at seven a.m.,” she says with a practiced apathy.

“Well, the door was ajar and I thought the temple might have extended its hours for Yulan.”

Yulan is Choi’s favorite day on the lunar calendar. The annual Festival of Hungry Ghosts, celebrated on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, is Halloween without the goofy costumes and free candy. The only trick-or-treaters are the ghosts, who for one night every year get a free pass to mingle with the living and help themselves to offerings of barbecued pork, roast duck, and free-flowing rice wine.

“Come back tomorrow, lah. The temple opens daily at seven a.m.,” the woman repeats impatiently as she approaches the door to close it. “Have a good night.”

Choi gets a better look at the woman as her face comes into the amber streetlight. He is surprised to see how young she is—no more than two or three years older than he. She has large downturned eyes, high cheekbones, and squeaky-white teeth. A veritable Maggie Cheung if it weren’t for her petite stature.

“Wait, is that an HKU sweatshirt you’re wearing?” Choi cheers. “I’m a freshman there. Poli-sci. What a small world!”

“It belongs to my older sister,” the girl explains. “She’s a journalism major. We wear each other’s clothes all the time.”

“My name is Choi. Do you work here? Do you live here?”

“Look, I’m closing up . . .” She demurs, grits her teeth, and continues, “You can call me Suze. I don’t live here, but my family runs this place. We all have to pitch in and take a few shifts a week. The temple closes at five p.m.”

“Then why are you here so late?”

“I . . . Well, today is Yulan and we had loads of visitors. It has taken me forever to finish up, that’s why.”

Choi senses an opening and offers, “Is there anything I can help you with? It’s only nine thirty and I’m already finished. I’ve got tons of time to kill.”

“Finished with what?” She sizes him up. “And what’s the deal with that?”

“Oh, this?” He shows her his flashlight and starts to flick it on and off. “I was in Tai Hang earlier to check out the famous nullah before I started wandering around and ended up here. The nullah is—was supposed to be haunted and I wanted to see it for myself.”

“You wanted to visit a haunted place on Yulan of all days?”

“That’s the whole point, ah! Years ago some children fell into the water and drowned. Since then, kids can be heard laughing and weeping in the middle of the night. At least that’s what I read when I googled it.”

The nineteen-year-old is a thrill-seeker. Every year, he visits one of the well-known haunted sites in Hong Kong, like Tsat Tsz Mui Road in North Point, Bela Vista Villa in Cheung Chau, and Hung Shui Kiu in Tuen Mun. Why pay money to go to those fake haunted houses at Ocean Park when he has free access to the real ones across the city? Last Yulan he snuck into the defunct psychiatric hospital in Sai Ying Pun and got a real adrenaline rush.

“So did you manage to run into any weeping children tonight?”

“Fat chance! Tai Hang has been gentrified beyond recognition with all those high-end restaurants and pretentious bars. The poor old nullah was paved over by the government and turned into a regular street. I should be the one weeping tonight!”

The girl chuckles. “Next time, perhaps you should check out Park’s Tower down the street. It was a movie theater before they tore it down to make way for an office building. I was told a couple of construction workers died in an accident during the redevelopment. Now the landlord has a hard time finding tenants because businesses are too scared to move in.”

“Is that right?” Choi chirps as he puts his other foot over the threshold. “Well, this place is pretty spooky too. Do you mind if I take a quick look around?”

Suze considers the request for a moment and relents. She gives the boy a half smile and ushers him into the

dimly lit main hall. Inside, the air feels musty and ancient, but the overpowering smell of incense soon takes over as they approach the altar.

“So this is the famous Tin Hau?” Choi marvels at the sheer size of the statue. “She mustn’t be very busy these days considering how few fishermen are left in Hong Kong for her to protect.”

The two settle into a corner that looks like a makeshift home office: a wooden desk, a telephone, and a pile of ledgers to keep track of donations. The naked lightbulb hanging from the ceiling swings to and fro, making every shadow on the walls rock like roly-poly toys. She offers her visitor a wooden stool before sitting cross-legged on the floor, leaning against a life-size statue of Guan Gong—the God of Justice.

“You said your family runs this temple. How did that happen?”

“A long time ago, my clan raised money to build this place after my great-great-great-great-grandfather supposedly witnessed a miracle when a red incense burner was washed ashore by a typhoon. Believe it or not, the temple used to look out toward Victoria Harbor. The shoreline wasn’t far from where we are until a huge land reclamation project created all this new land.”

“So your family owns the temple?”

“Yes and no. It’s our temple but we have to hand it over to the government eventually. We spent years negotiating with the bureaucrats and finally got them to agree to let us operate it for a few more years. Who knows what they’ll do once they get their hands on it. Tin Hau Temple Road is such prime real estate, and property developers have been salivating over it for decades.”

“I’m sure it’ll be fine. Isn’t the temple an official monument? No one will be able to touch it.”

“Don’t be so sure. You know what the name Tai Hang means?”

“It means a big ditch.”

“Precisely. The area is named after the famous nullah—the one you wanted to check out. But did the government care? Did it stop them from filling the ditch with concrete and turning it into a sidewalk? They even renamed the site—Tai Hang Nullah is now called Fire Dragon Path—as if to erase it from history. From our memory.”

Hong Kong Noir

Hong Kong Noir